D&D Druid: On Choosing Your Weapons and Armor

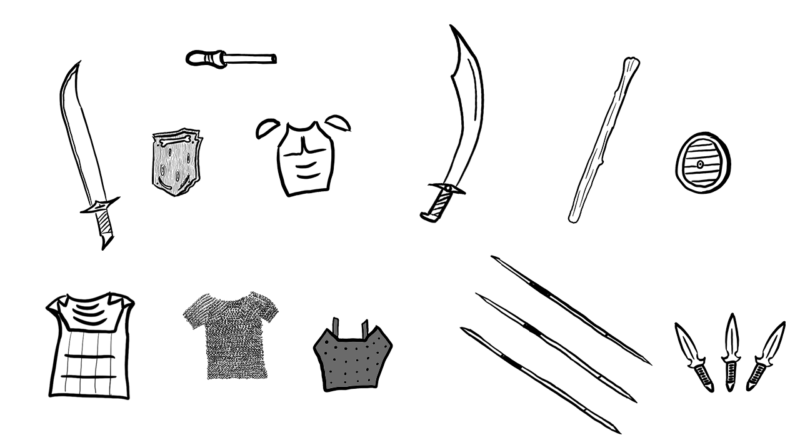

Generally in D&D, full spellcasters are squishy but powerful, and martial classes are chonkier but with less magical versatility. But then there’s druid (and cleric), who gets both! Druid’s equipment options are structured differently from most other classes. You’re only allowed to use a handful of weapon types, and you can’t wear armor/shields made of metal. But there are nevertheless some great options in your proficiencies. Today I wanted to discuss some common considerations/options available to you when you kit out your new druid.

And before we can discuss anything, there’s an important question you need to ask your GM. Because the rules are ambiguous on this important distinction and many people weigh in either direction:

“Are totem shields allowed?”

Let me explain. Like most casters, druids need to be holding a focus in order to cast spells. The rules are seemingly pretty clear on what’s allowed to be a druidic focus:

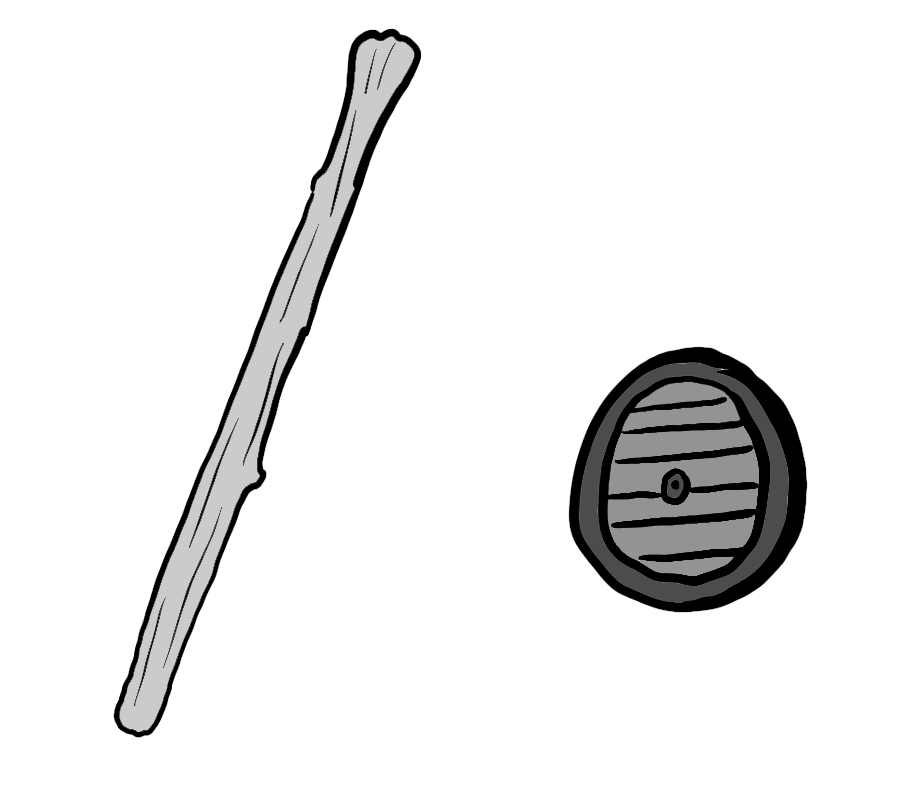

The first option that matters is the “staff drawn whole out of a living tree.” Almost every GM I’ve encountered will permit druids to use a quarterstaff to fulfill this parameter if they’d like. But the ‘totem object’ afterward is where the debate sets in. Druids are proficient with shields; could they summarily decorate a wooden shield and use it to cast spells? Shields are objects, after all. Your GM’s answer will determine what viable loadouts are available to you.

Loadout 1: Quarterstaff + Shield

This is the go-to druid loadout, probably the most iconic flavor of druid out there. It’s remarkably versatile; your quarterstaff is the among the highest-damage weapons available, and you can turn it into a magic weapon with shillelagh. Shillelagh-infused quarterstaffs scale off Wisdom instead of Strength, which is really important since Strength is a dump stat on druid. All in all, you really can’t go wrong with a quarterstaff. But, if your GM does allow totem shields, there’s a second option worth considering:

This is the go-to druid loadout, probably the most iconic flavor of druid out there. It’s remarkably versatile; your quarterstaff is the among the highest-damage weapons available, and you can turn it into a magic weapon with shillelagh. Shillelagh-infused quarterstaffs scale off Wisdom instead of Strength, which is really important since Strength is a dump stat on druid. All in all, you really can’t go wrong with a quarterstaff. But, if your GM does allow totem shields, there’s a second option worth considering:

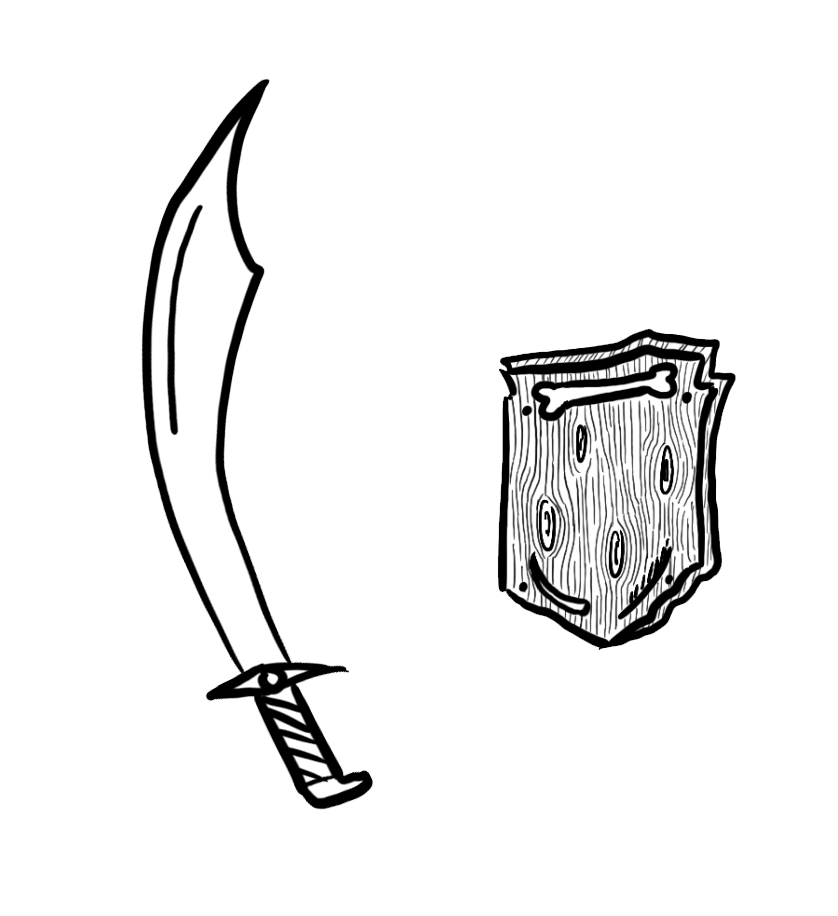

Loadout 2: Scimitar + Totem shield

Scimitars fill an interesting niche compared to quarterstaffs. As a finesse weapon, it lets you use your Dex instead of your Strength for both attacks and damage, which is always an upgrade for a druid. Dex (along with Con) is your secondary ability, meaning you’ll probably have put a few points there. And as a martial weapon, it deals the same base damage as a one-handed quarterstaff while using a more useful damage type (slashing over bludgeoning). This is my preferred loadout since I’d rather not spend a cantrip slot on shillelagh. And believe it or not, in their own way scimitars are just as iconic a druid weapon. Druids have been able to wield them since 1st edition thanks to the sword’s similarity to moon-shaped sickles.

A note on spellcasting components

Another thing you’ll need to keep in mind is whether you need a free hand for whatever spell you’re hoping to cast. Somatic and material components can be confusing, I recommend reading this official article for a full breakdown. But the gist is that you’ll occasionally need a free hand to cast a spell with either a material or somatic component (unless you take the War Caster feat), with your other hand holding your druidic focus. The ability to sheathe or draw an object as a free action mostly mitigates this issue. But that does mean you’ll occasionally be left with your non-druidic-focus item sheathed at the end of your turn. This is another plus-point for the totem shield, as I’d rather be holding a shield during my opponent’s turn than a quarterstaff, if I had to choose.

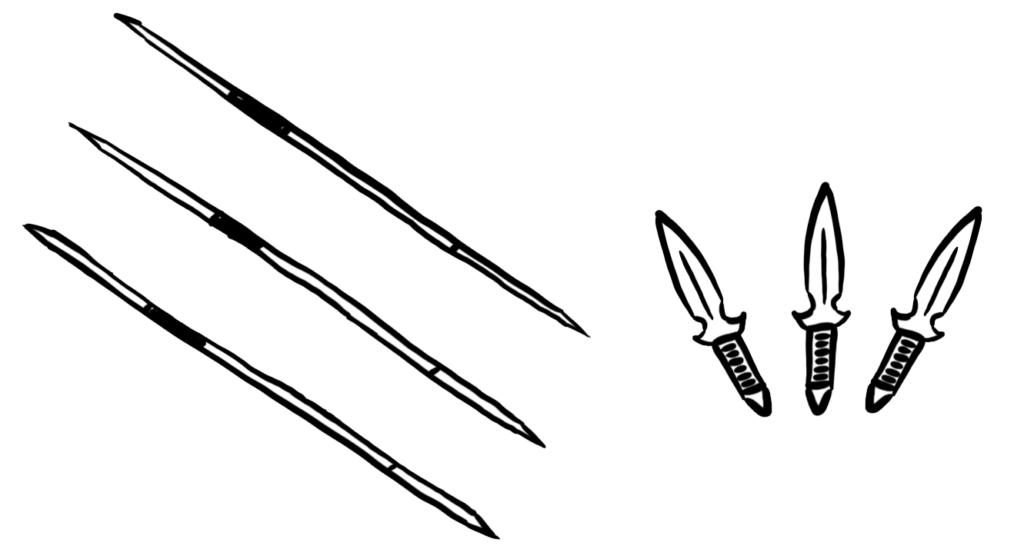

Ranged weapons: Javelins vs Throwing daggers

Now that we’ve discussed melee weapons, you’re going to want an emergency ranged option in your backpack for anti-magic situations. The two best ones available to you are javelins and (throwing) daggers. Javelins deal the most straight damage while also having the best range. But I honestly prefer throwing daggers for a couple reasons. They’re finesse weapons, meaning you can once again use Dex over Strength, and this usually offsets the lower damage die for me. Plus they’re easier to conceal, weigh less, and have more non-combat utility. In any way, this isn’t a very crucial decision as you’re likely going to use magic for ranged damage 99% of the time.

Choosing armor

As mentioned before, druids can’t wear metal armor, which pretty severely limits your options. Studded leather is the best all-around choice, conveying no penalties while still having a halfway-decent armor value. (Its description doesn’t say the studs are metal, so presumably yours are made of bone or chitin or something.) Every better armor in the Player’s Handbook specifically mentions metal parts except spiked armor or ring mail, so those are options if you’re okay with the weight and stealth disadvantage. (Remember you dumped Strength, so you might actually struggle with encumbrance wearing 40lb armor. Though on the flipside, you can always shapeshift or cast pass without trace for stealthy situations.) Outside these, you’re reliant on your GM giving you rare or unusual armors that bypass the metal restriction, like dragon scale mail.

In practice, I purchased studded leather the second I could afford it and never took it off for the rest of the campaign. Druids get enough healing, shapeshifting, and shielding that I didn’t find armor too pressing an issue.

However, before we wrap this article I have to mention…

Barding

Wait, what?

Yeah, there’s actually a potential argument for lugging around barding in your backpack if you can spare the space. The rules for Wildshaping state that, “you choose whether your equipment falls to the ground in your space, merges into your new form, or is worn by it.” (Emphasis mine.)

This means you can legally fashion some armor for your favorite combat form and auto-equip it during Wildshape to buff that usually-low bestial AC. The primary downside is the logistical question of where the hell you were carrying it. And the fact that barding weighs a ton and you probably dumped Strength. But hey, its doable.

Conclusion

To be perfectly honest, almost everything we discussed in this article is pretty minor. Druids are spellcasters who can turn into bears, they don’t really care what’s sitting in their backpack while biting someone’s throat out. Even a fully-optimized combat quarterstaff will simply be functioning as a magic wand for the majority of your player experience. But you never know what a D&D campaign will throw at you, and it’s nice to have your gear sorted out for unexpected contingencies. And the superfluity can be its own perk, because you can freely pick whatever gives your druid a cool personal or sentimental theme. Gutter, the pirate druid I’m playing, casts her spells using a belaying pin because I thought it was funny. Keep your mind open and go with whatever sounds right in your heart!

Note about spellcasting, you don’t need to use inexpensive material components if you’re using a spell focus. This is why pure spellcasters get the choice between a component pouch or a focus from the quick equipment choices at character creation– they’re effectively the same, but a focus is just plain better since you don’t have to refill it. If you have a focus on hand, the only time you need a material component for a spell if is the material is listed with a price, such as with the 100gp valued pearl for casting Identify.

Why do component pouches exist then? Because not everyone that can cast spells can use a spell focus– Eldritch Knight, Arcane Trickster, and base Ranger all have to use material components and don’t have a focus for their casting.

Oh and a hand holding a spell focus can be used for the somatic component as well. So a Druid with a shield plus staff or (if the DM allows a totem shield) scimitar, wouldn’t have to spend an object interaction to stow a weapon or shield to cast any spell.

The rules seem strange on that front, specifically on the matter of spells that only require a somatic component but not a material one. To quote examples from that article I linked above:

“A cleric’s holy symbol is emblazoned on her shield. She likes to wade into melee combat with a mace in one hand and a shield in the other. She uses the holy symbol as her spellcasting focus, so she needs to have the shield in hand when she casts a cleric spell that has a material component. If the spell, such as aid, also has a somatic component, she can perform that component with the shield hand and keep holding the mace in the other.

If the same cleric casts cure wounds, she needs to put the mace or the shield away, because that spell doesn’t have a material component but does have a somatic component. She’s going to need a free hand to make the spell’s gestures. If she had the War Caster feat, she could ignore this restriction.”

Now I admit this stance completely baffles me, as it suggests somatic-only spells are somehow harder/more-restrictive to cast than S+M spells, but Jeremy Crawford wrote the article so I guess that’s the way it is. Unless I’m somehow misinterpreting that ‘cure wounds’ example, it looks like casters can only use their focus-holding hand for somatic components on spells that ALSO have material components.

Crawford is definitely an expert. Upon closer inspection, I think I see my mistake and can explain why those spells are supposed to be more difficult:

Somatic components are described as movements that might include “forceful gesticulation *or* an intricate set of gestures.” (PHB203)

We should then assume that, if a spell requires materials or a focus, the complexity of any somatics is basic– say, lifting your emblazoned shield aloft to rouse your allies with Aid. Whereas a somatic spell without material requirements has intricate movements, like mudras. The point is a bit moot though unless you’re trying to cast a spell as a bonus action and preserve your action for something else. Sheathing your weapon is an object interaction, then drawing on your next turn is another object interaction. At worst, you lose out on being able to deliver a harder-hitting opportunity attack if you cast Cure.

I don’t think I’ve seen any table actually play this out in practice, but it definitely adds a strategic element to the game, albeit a bit finicky for the streamlined design. That’s a bit of the classic D&D thumbprint for you though– magic was a BEAST in old editions but needed much more upkeep.

Good points! It always seemed weird to me the writers took all this time to come up with components for every spell in the game, and then 99% of casters get to just ignore them. But it adds a lot of flavor to each spell, and matters for the partial-casters you mentioned (or people who took Magic Initiate)

The Animated Spellbook did a really interesting analysis on why Goodberry should be disregarded from games, particularly because it completely circumvents the survivalist genre. The example cited was a campaign where, after escaping prison and losing all of their gear, the party has to navigate a wilderness while evading pursuit. Constitution checks for exposure, skill checks for traversal, and party decisions on whether to hunt, hide, or rest made for an intense story beat.

Until the ranger finally found the sprig of mistletoe he needed to cast Goodberry.

But that just shows one way having a clear material component listed can be really interesting! If that adventure took place in a desert or any climate where mistletoe just doesn’t grow, that completely changes what spells they could look to cast without access to a pouch or focus.