Filling in the blanks in FTL

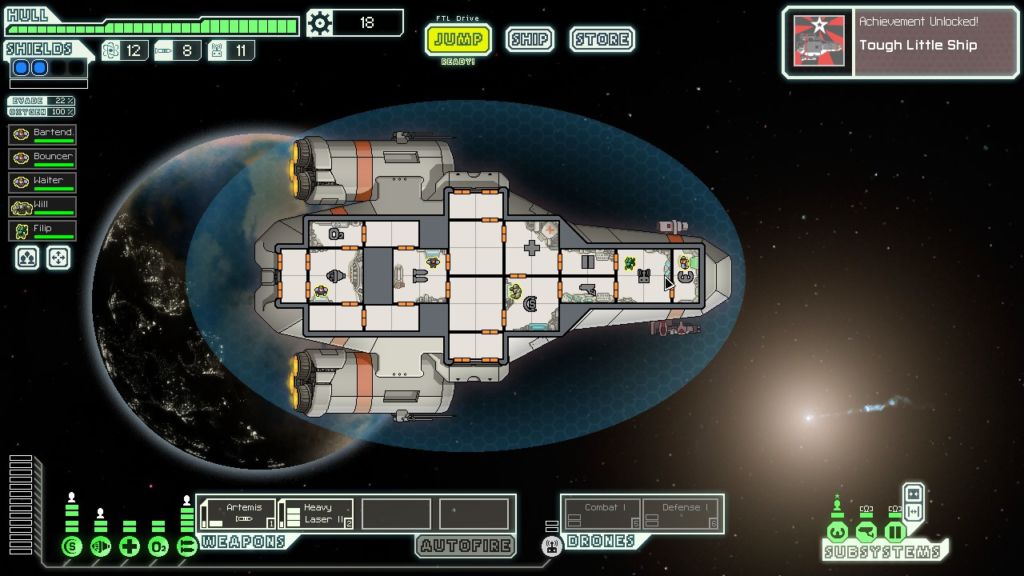

I was playing FTL: Faster Than Light the other day, and I decided to have a bit of fun with the names. I named my Kestrel The Bar, and my starting crew members as Bartender, Bouncer and Waiter.

The backstory was, they were a bar-on-a-spaceship that serves people across the galaxy while flying around. One day, the bartender overheard two Rebel agents discussing some rather sensitive intel and the Rebel’s plans to hold their home planet hostage. Once they left, the three of them closed their bar, readied their arms (space pirates want space rum but doesn’t like to pay), and set off to warn the Federation. However, someone tipped those pesky Rebels off, and the Rebels are now in hot pursuit.

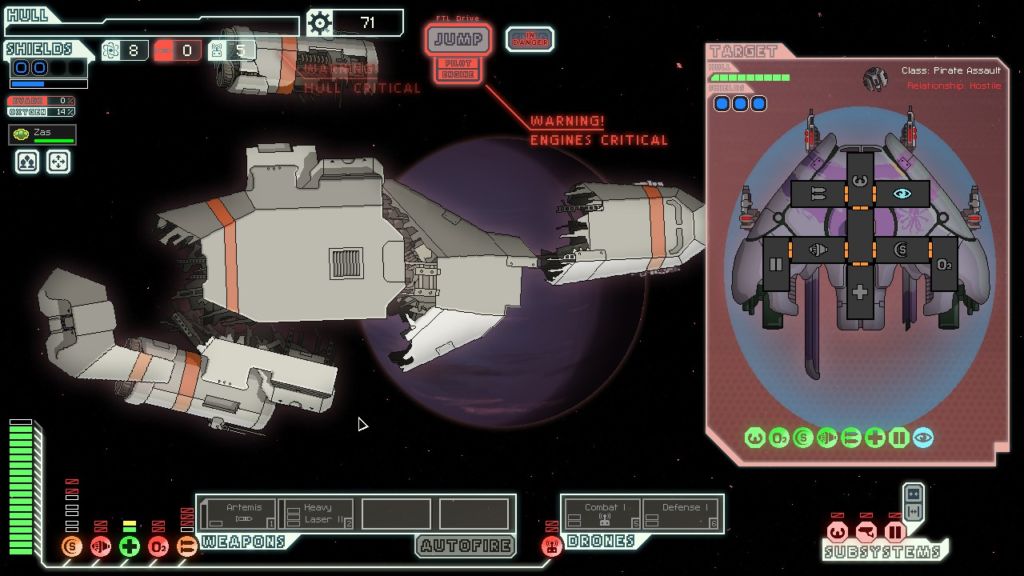

However, that wasn’t what I’m here to talk about today. What I’m here to discuss is how games like FTL create a story simply by having a general premise and just letting events unfold. Bartender turned up to be quite a competent captain and led the crew through multiple near misses. Bouncer manned the weapons and Waiter serviced the engines. They have couple of fights, new crew members come and go, as they tried their best to get to the Federation. Alas, they were cornered by some rather pesky pirates and died without delivering the intel.

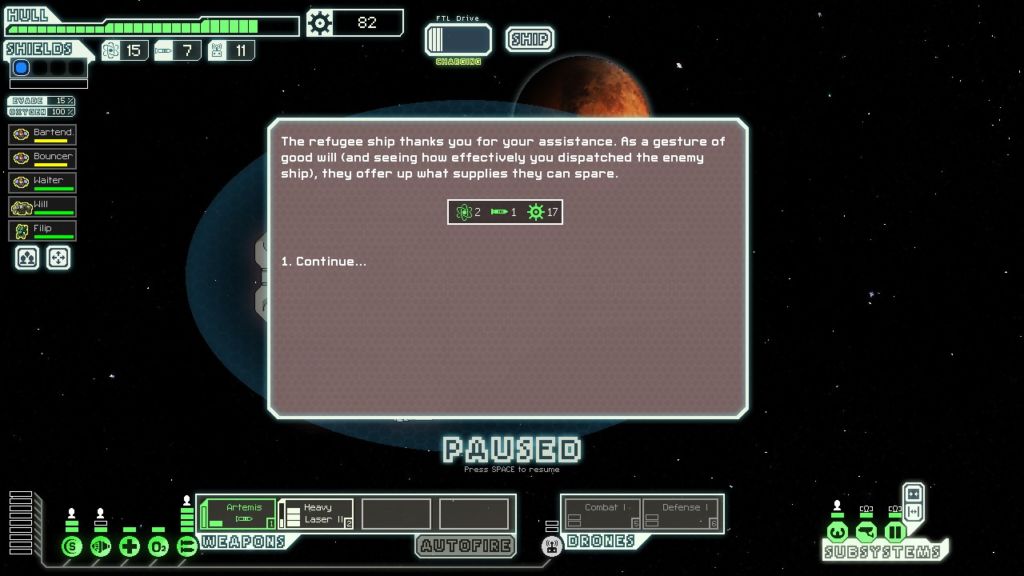

The thing is, by setting up a premise and leaving a lot of blanks, a player will start to fill in the blanks by himself. I mean, have you ever played Pokémon? I love my Amaterasu because of what we went through together. Aabicus and his Raticate Brenna shares an unbreakable bond that transcends generations. I am not, and will not discount how we feel, because our feelings are genuine, but if we were to be extremely cynical about it, we are just adding meaning to a set of events controlled by RNGs. There is no story attached to our digital friends. Game Freak probably doesn’t even like what we love. There is absolutely nothing that warrants the emotions we have towards them, nor does it deserves us recounting the tales of adventure we have with them.

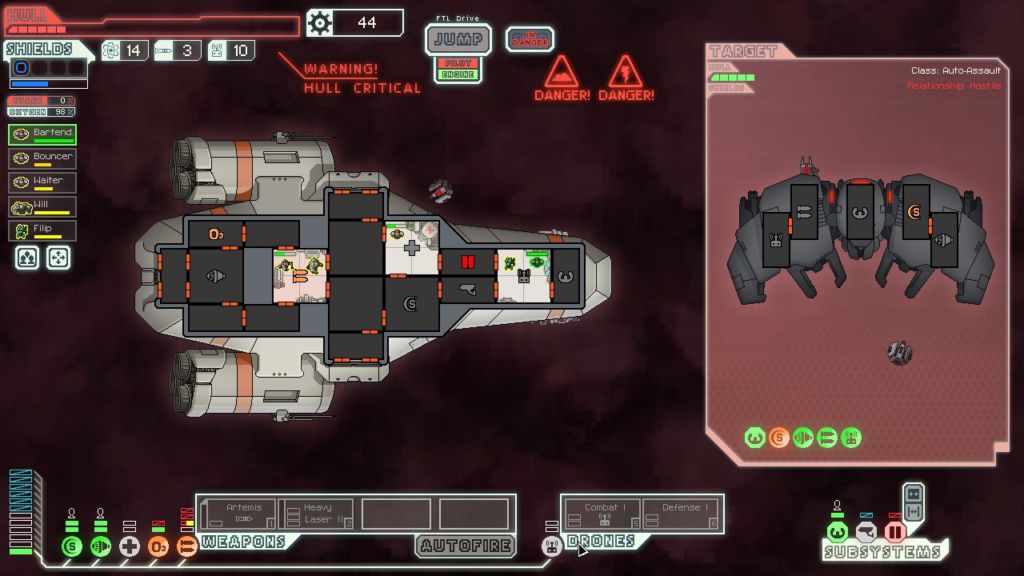

By the same token, there isn’t any point in feeling anything when The Bar blew up. Except a vague sense of disappointment because I failed to reach the end of the session to unlock my new spaceship. However, I was genuinely upset when Waiter died trying to fix up the engine so that the ship can evade enemy shots. And I was heartbroken when, two flights later, Bartender died, my two-star pilot and ever-reliable captain. And when Bouncer died by the weapons control, all is lost.

By leaving some blanks for the players’ imaginations to run wild, as well as providing enough things to happen and making them crucial to the game, it is actually possible to foster a sense of attachment. Even if it’s never the intention of the developer. Since FTL has rather short sessions and the slate is scrubbed clean after every session,the effect is somewhat diminished. But for longer games like XCOM: Enemy Unknown, the soldiers’ long struggles against the aliens under your command amplifies this effect a lot more.

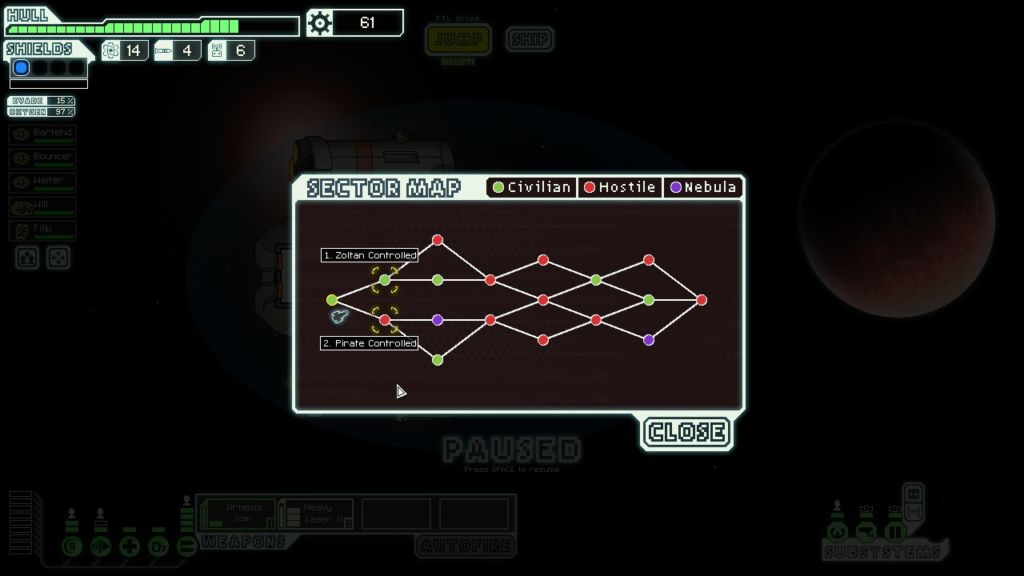

By setting up an environment for a story to grow by itself and letting the audience and the game fill in the blanks, this creates a form of interactive storytelling where no one knew what happens, since there is no way anyone, not even the devs, can know what will occur at any stage of the game. Granted, it probably won’t be an epic tale full of twists and turns, since those actually need good writers to write the story and manage the pacing and narrative, but it can still be a rather gripping tale.

And the permadeath aspect of FTL might actually add to the effect too. In a story-driven game, the main character (player character in most cases, if not all) will never die unless the plot demands it, so that the story can continue on. This creates a safety net for them, and lowers the stakes of the story. No matter how scary or powerful the planet-sized final boss seems, there is always a feeling at the back of your mind that you will survive no matter what, even if you “died” and was sent back to the previous checkpoint.

However, permadeath removes that safety net. It makes it less likely for you to survive anything. An ion storm that might be a minor nuisance in other games turns into a death trap in FTL. It raises the stakes by making it rather clear that you will most likely die. This also means that the one time you did manage to break through and win will be much more notable, when you contrast it with the number of ways you could have (or most likely did in an earlier playthrough) died.

And unlike stories with branching paths, this one is truly organic. For the former, while there are choices you can make that will change how the story progresses, it will still follow a predestined path in the end, just that there is more than one in the game. While in our case here, there is no path. We’re walking on uncharted territory here.

The blank space that FTL’s premise leaves behind creates room for a story to develop. As a video game storytelling method, this could be worth exploring. Create a world where things can happen, set up a premise, and let go. This is something traditional media can never imitate, and thus it is something unique to videogames that the medium should adopt in more games.